How the heck did we train guinea fowl to return to their coop?

I’ve never seen more ticks in the Hudson Vally than I did in the summer of 2020. After a month of pulling a tick off of me every day, I decided it was time to go to war against the tick population on the farm. My solution was to raise a flock of well-trained mercenaries: guinea fowl are known for being excellent tick hunters. In a previous post, I wrote about raising these day old guinea keets in a brooder.

The odds weren’t in my favor. I bought just a small flock of forty guinea keets and we have about three hundred acres of farmland here in New York. If I built a coop in the center of the farm, I wasn’t sure if they would hunt in a large enough radius to cover the farm. Instead, I decided to build a mobile coop that I would park in different spots on the farm throughout the year. In order for this plan to work, the guinea keets would need to return to the coop after a day of running wild on the farm.

The Mobile Coop

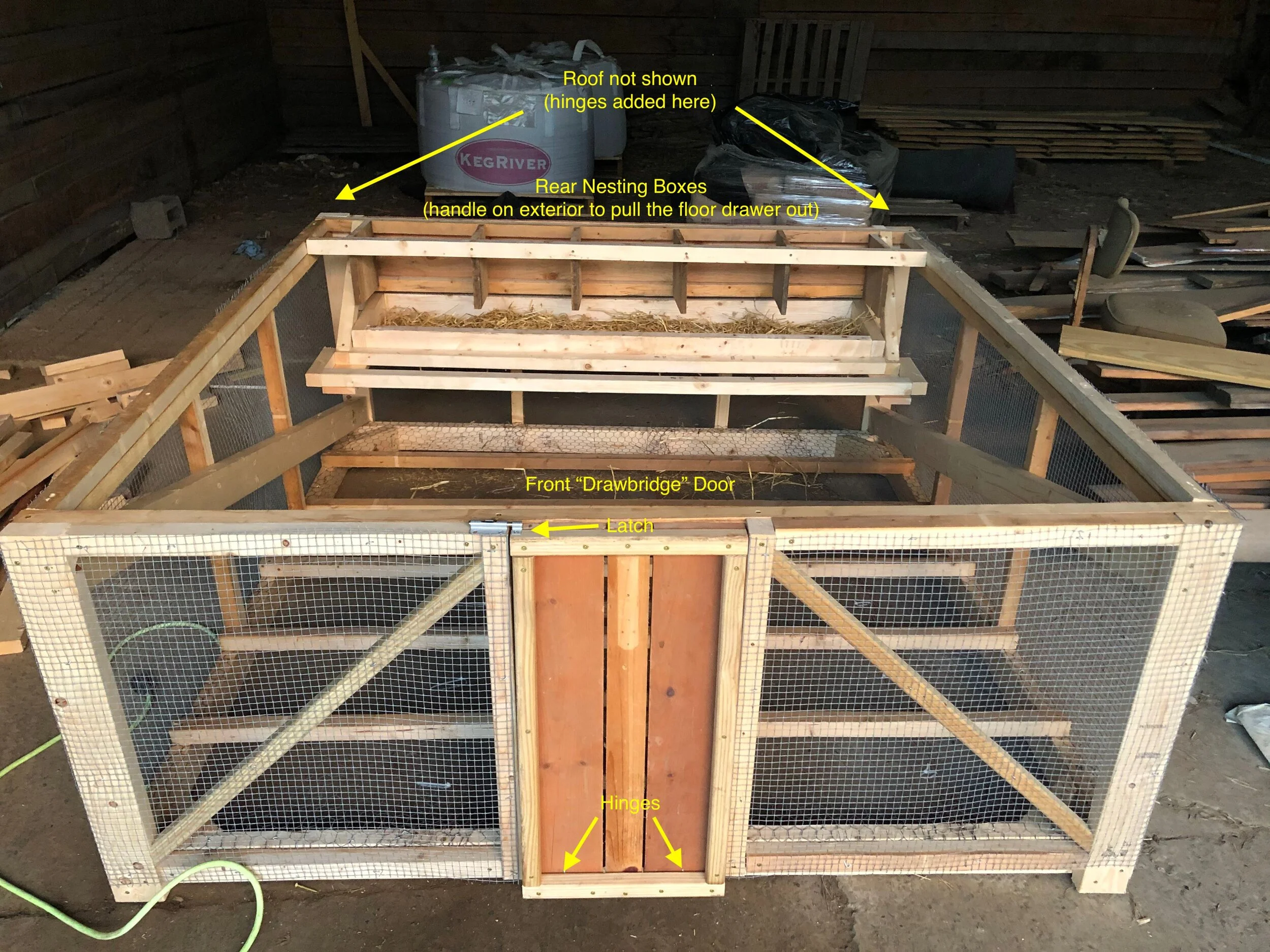

I built a mobile coop that was a slight variation of the chickshaw designed by Justin Rhodes. This mobile coop had a few fun features:

A hinged roof that made it possible to add feed or water to the coop without the birds escaping

A front drawbridge-style door that allowed the birds to enter or exit freely when the door was open

A set of nesting boxes in the rear that made it easy to collect eggs without getting pecked at.

Wheels and a pull bar, allowing one person to relocate the entire flock.

The coop, however, was designed for chickens. Chickens don’t fly. Guinea fowl don’t exactly fly either, but they’re more determined to try than chickens. When they flap their wings like crazy, they do manage to get off of the ground for a few seconds. Because of this, there are a few changes that I might make in the next coop that I build. I’ll explain this a little further down in this post.

Training the adolescent guinea fowl to return home

Once the guinea fowl were a few weeks old, I moved them from the brooder to the coop. It’s important that they know the coop as home from a young age.

I kept the birds in the coop for another couple of weeks and didn’t allow them to exit until their bodies were about the size of a baseball and their wings had started to feather. I’m writing this post almost a full year later and my memory is a little foggy, but I think they were about six weeks old before I allowed them out of the coop.

My general approach to training them to return to the coop was to make sure that the coop felt like home. There are two very important pieces to this approach:

Home is where you eat. While they did graze on bugs and greens outside (this was the point, after all), I never fed them grain outside. I kept their feed trough inside the coop filled at all times.

Home is where your family is. Guinea fowl are flock birds and so they naturally want to stay with the flock.

On day 1 of training, I placed just two (of forty) birds outside. I thought they might run for it, but they instead spent the whole day crouched in the grass underneath the coop. They had the whole world available to them, but they were terrified to leave the rest of the flock that was still in the coop. Make sure you have a source of water by the coop for these birds outside.

The trickiest part of this project was getting the birds to return to the coop each evening. At this point, the little velociraptors were too agile to easily catch by hand. With the help of my old man, we developed an approach to herding them back into the coop. We lowered the front door, offering a ramp for the birds to walk back into the coop. The two of us were each armed with two ruler-length sticks to herd the birds. One of us stood a few feet from the front door. The second person then walked in a circle from the back of the coop towards the front of the coop, using their sticks as guardrails to nudge the birds towards the front. As the birds near the front door, both of you now need to use your sticks to block all possible paths, leaving no option for the birds other than to walk up the ramp into the coop. This was a bit of circus for the first few week or two. It took us dozens of tries at first. The birds slowly became more comfortable with this process, and we developed a bit of a skill, so soon we were able to herd the birds back into the coop with just one or two laps around the coop.

We repeated this for a few more days, randomly selecting two birds from the flock each day. We then doubled the outside flock to four birds. Then eight. By the third week of this training routine, we allowed half of the flock to exit the coop in the morning. This was a critical point because there were as many birds outside of the coop as there were inside the coop. I was worried that the outside flock would feel comfortable to venture off on their own. They were a bit more adventurous at this point, but they did still stay close. To reinforce this, we continued to let only half of the flock out each day for another couple of weeks.

By the time the birds were about two months old, opened the door and let the whole flock go. To our surprise, by dusk we found them all back near the coop and many of them were sitting on the coop.

Challenges and Learnings

As the birds became older and more adventurous, there were nights when some or all of the flock did not return to the coop. We found that they became increasingly driven by daylight hours. They were nowhere to be found in the early evening, but they reliably returned to the coop by dusk. Herding them back into the coop in the dark was significantly more challenging. The next time I raise guinea fowl, I would like to try a coop design that allows them to freely enter and exit on their own schedule, while still offering some protection from predators.

We have two main predators in the Hudson Valley: coyotes and large birds (hawks and eagles). The guinea fowl are lighter than both of these predators, and the mature guinea fowl are able to fly about ten feet off of the ground. I would like to try a version of a coop that always allows the birds to enter through the top of the coop. To do this, I’m imagining a roosting bar that they may fly up to and then hop into the coop from there. To protect from coyotes, this roosting bar should collapse under too much weight. The aerial predators are trickier to protect against, but I’m much more concerned about the coyote pressure.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact us.